A streamlined but structured approach to analysis

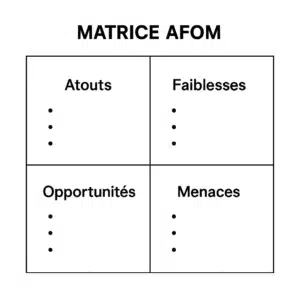

The SWOT matrix (Strengths, Weaknesses, Opportunities, Threats) is a strategic analysis tool that helps assess the current position of a company, product, project, or even an individual by crossing two essential dimensions: internal analysis and external analysis. The goal is not merely to compile a list, but to structure a thought process geared toward action and decision-making. It is a powerful tool, all the more so because it is easy to understand but demanding to complete effectively, as it requires confronting objective reality with subjective perceptions.

The matrix is presented as a four-quadrant table :

- Strengths : what the organization does well, its resources, and distinctive advantages.

- Weaknesses : its internal limitations, gaps or dysfunctions.

- Opportunities : trends, developments or openings in the external environment that could be favorable.

- Threats : external risks, structural obstacles or potential disruptions.

This dual internal/external perspective is the core strength of the SWOT: it forces a cross-analysis between what is within our control and what lies beyond it.

The rigor of a diagnosis: balancing clarity with foresight

The effectiveness of a SWOT matrix depends on the quality of the initial diagnosis. Too often, this tool is filled out in an automatic or superficial way, without serious confrontation with actual data, on-the-ground perceptions, or weak signals. A good matrix goes beyond echoing dominant ideas; it must reflect a nuanced understanding of the competitive, technological, societal, and economic environment, along with an honest view of internal dynamics.

Strengths should be expressed as comparative advantages, not general statements. These might include specialized expertise, a loyal customer base, a strong brand, recognized technical know-how, or a culture of innovation. Conversely, weaknesses must be addressed with unflinching honesty: slow execution, reliance on a single channel, lack of key skills, rigid organization, technical debt, or damaged reputation.

On the external side, opportunities may arise from various factors: favorable regulatory changes, emerging technologies, shifting consumer expectations, competitors’ weaknesses, or underdeveloped geographic markets. Threats, on the other hand, require anticipatory thinking: industry disruption, new entrants, geopolitical instability, changing behaviors, or resource tensions.

A cross-analysis to guide decision-making

The key value of the SWOT matrix lies in its ability to generate actionable insights through the confrontation of elements. It’s not just about filling in four boxes, but about extracting meaningful combinations. This leads to four types of strategic responses:

- Offensive Strategy (Strengths + Opportunities): How can we leverage our strengths to take advantage of market openings?

- Defensive Strategy (Strengths + Threats): How can we use our strengths to shield ourselves from external threats?

- Turnaround Strategy (Weaknesses + Opportunities): How can we overcome our weaknesses to seize new opportunities?

- Avoidance Strategy (Weaknesses + Threats): How can we minimize our vulnerabilities to avoid being exposed to future risks?

These cross-analyses allow for the formulation of scenarios, testing of potential directions, and prioritization of corrective actions or offensive initiatives. The matrix thus becomes a tool for arbitration, resource allocation, and organizational transformation.

Practical applications in businesses, start-ups, and the public sector

The SWOT is used in a variety of contexts: product launches, brand repositioning, entering new markets, fundraising, organizational audits, or even territorial planning. In a start-up, it can help identify the key success factors to strengthen before targeting a new segment. In an industrial SME, it assists in formalizing a diversification strategy. For a public-sector actor, it is often used to inform decisions related to urban planning, mobility or health policies.

In any cases, the matrix facilitates a shared overview among various stakeholders. It highlights blind spots, helps break away from purely hierarchical or intuitive thinking, and provides a structured foundation for reasoning, convincing, or documenting a roadmap.

Common pitfalls to avoid

Although accessible, the SWOT matrix is not immune to methodological missteps. The most frequent error is filling it out imprecisely, without evidence, or using tautologies. Saying “our strength is quality” or “the threat is competition” is often meaningless without proof, comparison, or metrics. A best practice is to support each point with verifiable facts, studies, indicators, or user feedback.

Another pitfall is confusing internal and external factors. For example, “the rising cost of raw materials” is not a weakness but a threat. Similarly, “our lack of brand awareness” is an internal weakness, not an external threat. Maintaining this distinction is essential to enable valid cross-analyses.

Finally, a SWOT matrix should never remain static. It must be revisited regularly to reflect changes in context, resources, competitors, and market expectations. It is a living document—a steering tool—not a one-time stylistic exercise.

Integration with Other Strategic Analysis Tools

The strength of the SWOT matrix lies not only in its ability to synthesize a situation but also in its ability to interact with other strategic tools. When integrated into a broader toolkit, it becomes a central interface between analysis, decision-making, and action. In this way, it gains depth, nuance, and forward-looking capability.

Let’s take an example of its combination with a PEST analysis. PEST provides an in-depth mapping of the macro-environment, distinguishing six key dimensions: Political, Economic, Socio-cultural, Technological, Environmental, and Legal. These elements feed directly into the opportunities and threats quadrants of the SWOT matrix. For instance, a newly identified strict environmental regulation in the “Legal” dimension of PEST can be considered a threat in SWOT, especially if the organization is lagging behind on such issues. Conversely, the rise of more ethical consumer behavior observed in the “Socio-cultural” dimension can represent an opportunity for a company ready to respond. PEST thus acts as a rigorous and structured external enrichment filter.

Another effective combination is the intersection with the BCG matrix. This tool positions a company’s various activities or products based on two axes—relative market share and market growth—and helps determine where to focus resources. The SWOT analysis then takes it further: for each activity categorized as a “dilemma” or “dead weight,” it can clarify internal weaknesses that limit potential or external threats that must be anticipated. Conversely, a “Star” activity may, through SWOT, reveal key strengths to consolidate in order to maintain its strategic position.

Integrating a perceptual (or positioning) map is just as relevant. By plotting a brand, product, or offering along axes such as “perceived price” and “perceived quality” or “innovation” and “safety,” one visualizes its relative positioning compared to competitors. SWOT then identifies the internal resources (strengths) that support this positioning or, alternatively, exposes structural weaknesses that make it unstable. This enables the development of stronger differentiation strategies, grounded in real factors rather than isolated perceptions.

Michael Porter’s value chain analysis offers an operational and detailed view of the various internal activities of a business—logistics, production, marketing, services, and so on. When the SWOT is enriched using this analysis, it becomes possible to precisely identify optimization points within processes, differentiating competencies, or bottlenecks. This allows for a shift from a general strategic diagnosis to concrete actions for performance improvement.

In strategic marketing, the SWOT matrix is a powerful ally for segmenting a market based on the company’s specific strengths: it helps determine in which segments current strengths hold the most value, or where weaknesses could become significant liabilities. It also supports product positioning by showing how internal characteristics (R&D, brand image, after-sales service, etc.) can—or cannot—meet the needs and expectations of targeted segments. It helps to make positioning decisions more objective and to support them with facts.

In project management, SWOT is a strategic framing tool from the very first steps. It helps outline the project’s success conditions, anticipate critical risks, and identify required resources or key warning signs. It structures discussions around the business case and allows stakeholders to align around a clear, shared, and context-aware foundation.

So, the SWOT matrix becomes much more than a diagnostic tool: it acts as a strategic hinge, capable of connecting complementary tools and translating analysis into coherent operational decisions. It embodies a systemic approach—one of a strategy that is constructed, articulated, and managed across multiple layers of analysis.

Toward an Enhanced and Dynamic SWOT

With digital tools, SWOT can evolve into a more interactive, visual, and collaborative format. Platforms now allow stakeholders to co-create the matrix in real time, attach supporting documents (evidence, links, data), prioritize elements, or even integrate it into a strategic management dashboard. Some extensions, powered by AI, can automatically analyze information sources to generate relevant points for each quadrant.

SWOT thus becomes a dynamic tool for strategic dialogue—no longer a static table to fill, but a foundation for steering decisions, investments, and transformations based on a shared truth.